“Stress is a physiological or biological response to stressors.”

We have started a mini-series on stress management education as part of our efforts to combat stress.

Many individuals experience stress and struggle to find effective coping methods.

There are effective and healthy approaches to managing stress. We want more people to know about them, apply them and live happy, healthier lives while also letting people know the wrong ways to deal with stress so they avoid them altogether.

As more individuals become knowledgeable about stress, its effects, and effective coping mechanisms, there will be a significant decrease in the number of individuals severely affected by chronic stress.

Our mini-series on stress management will rely heavily on research and expert opinions.

We will be making a lot of references to recent research on stress management and also cite expert opinions on how to manage stress effectively.

Today, we’ll be taking a brief look at the physiology of stress—how the body responds to stress.

The World Health Organisation defines stress as mental tension or worry from dealing with a challenging situation.

Stress is natural and is even vital for our survival.

A good dose of stress gives us the motivation and impetus required to get things done.

It becomes a problem when it becomes prolonged (chronic stress) and is managed poorly.

Stress may emanate from our minds, but it also has a wide-reaching effect on our physical bodies (physiology).

It can affect the body’s cardiovascular, digestive, neurological and other vital systems. And if allowed to continue its assault on these systems, many complications will arise.

The Simple Physiology Behind Stress

The Stress Response: Fight or Flight

When you encounter a stressful situation, your body kicks into action with what’s known as the “fight or flight” response–this is your body’s way of preparing to deal with potential danger or threats.

It’s a survival mechanism that helps us face challenges by releasing certain special hormones (cortisol, catecholamines, vasopressin, etc).

When we were still “wild men”, living in the jungles, hunting, and running away from wild animals, these hormones were the chemicals that ensured we survived those harsh conditions.

Today, we may not have to run from dinosaurs or hunt for food with spears and bows and arrows, but we still face a different kind of stress–modern stress.

The fight or flight mechanism still plays much in our modern society.

Command Center: The Brain

It all starts in the brain.

When faced with a stressor or stressful situation, your body receives signals from various sources such as your eyes, ears, skin, or a combination.

The information is sent to the amygdala, a specialised area in the brain that contributes to emotional processing.

The amygdala is part of the Limbic System in the brain that ties emotional meaning to our memories and handles decision-making.

Interesting Fact: Research has shown that there is a positive correlation between the size of the amygdala and the amount of social interaction a person has. Specifically, the more social contacts and groups a person belongs to, the larger their amygdala tends to be.

(Bickart, Wright, Dautoff, Dickerson, & Barrett, 2011).

When the amygdala perceives a stressful situation, it sends distress signals to the hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus now communicates with the body through the autonomic nervous system, consisting of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

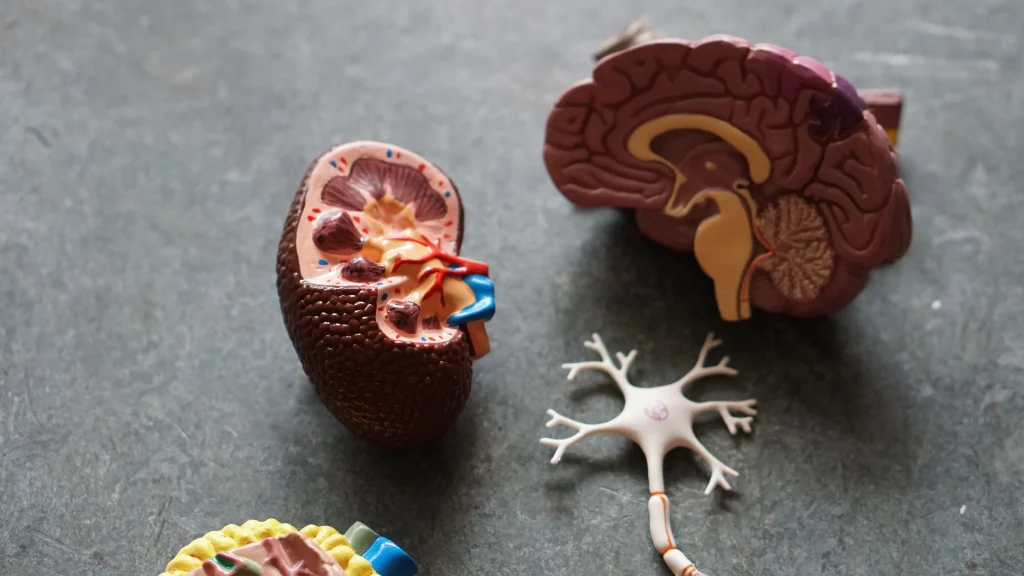

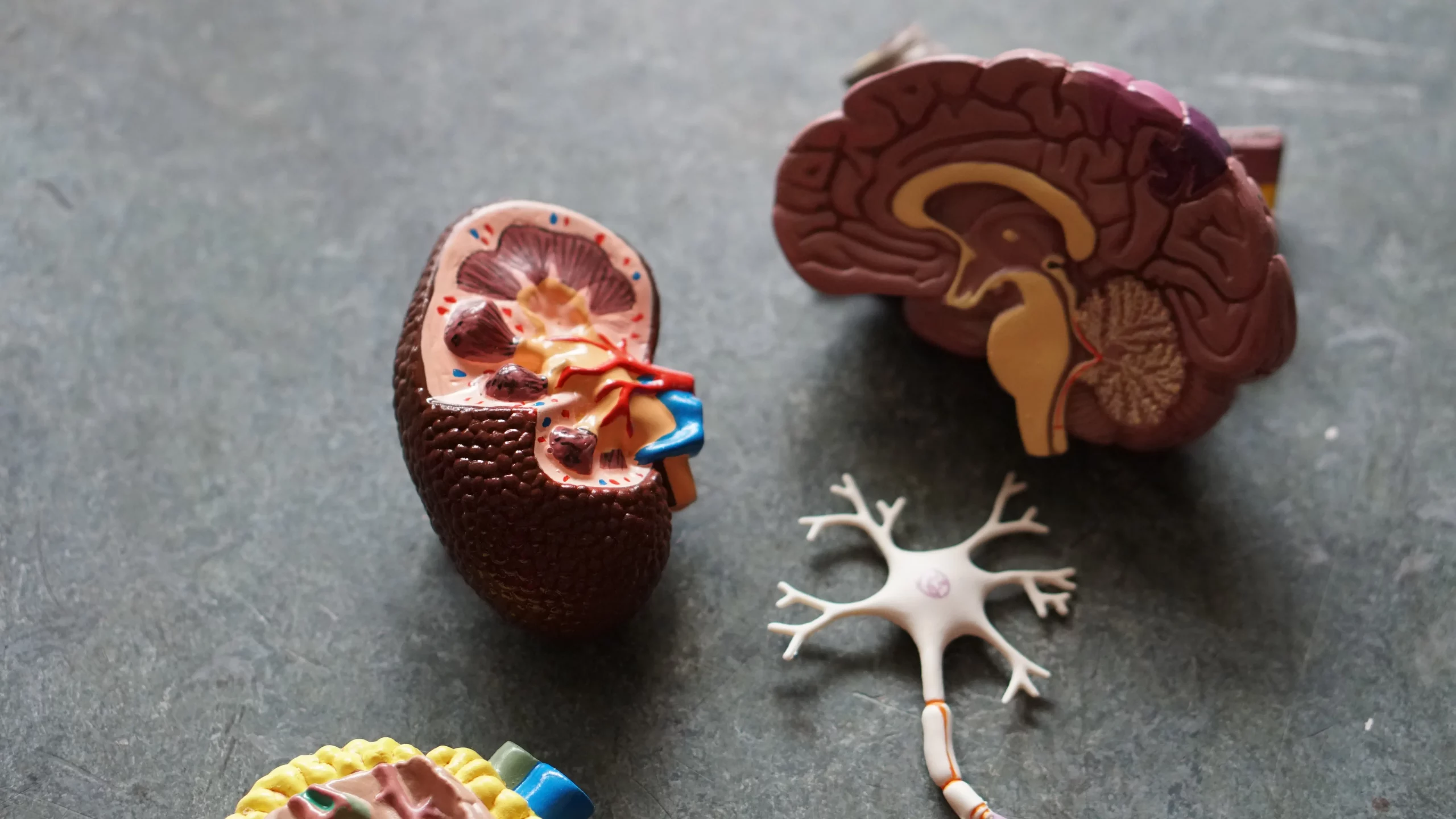

Through the sympathetic nervous system, the hypothalamus activates the adrenal glands, which secretes special hormones, like epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and cortisol.

Adrenaline Rush: The Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands, located atop your kidneys, release a surge of hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol.

These hormones function as messengers, relaying crucial instructions to different body parts in preparation for action.

Heart Racing and Muscles Tightening: Cardiovascular, Muscular Responses & Other Physiological Responses

As adrenaline courses through the veins, the heart rate increases, pumping more blood to the muscles and organs.

Pulse rate and blood pressure go up.

Breathing is faster, increasing oxygen uptake to the brain and increasing alertness, sight, hearing, and other responses become sharper.

Epinephrine also triggers the release of glucose (blood sugar) into the bloodstream, supplying energy for action!

These intrinsic actions happen so fast that you aren’t even aware. In fact, what happens between the amygdala and hypothalamus is so swift and efficient that it starts even before the brain’s visual centres have had a chance to fully process what is happening.

The Second Phase: HPA Axis & Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

After the initial rush of epinephrine fades, the HPA axis, which includes the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands, is activated to continue the stress response system.

The HPA axis depends on a sequence of hormonal signals to maintain the activity of the sympathetic nervous system.

Suppose the brain continues to perceive something as dangerous. In that case, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which triggers the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

The hormone travels to the adrenal glands, which then release cortisol.

The body stays on high alert (with all the heightened physiological changes we mentioned earlier). When the threat passes, or the stressor is no longer there, cortisol levels drop.

The parasympathetic nervous system then inhibits the stress response.

The Aftermath: Recovery

Once the stressor is gone, your body gradually returns to its normal state.

The adrenal glands stop pumping out excessive hormones, your heart rate slows, and your muscles relax.

Chronic Stress: Long-term Effects

While the stress response is a natural and helpful mechanism in the short term, constant stress can take a toll on your body.

As discussed in our introduction, chronic stress has been linked to various health issues, including heart problems, weakened immune systems, and mental health disorders.

This mini-series aims to help more people understand stress and provide them with up-to-date scientific information on stress management.

When people know what stress is and how to manage it, they can take better care of themselves when they find themselves in stressful situations.

In the next part, we’ll look briefly at the basic physiology of chronic stress.

If you don’t want to miss it, kindly subscribe below (in the footer section). We’ve got a lot we would like to share with you.

Drop Your Comment